In the Hellenic Age, the Greek society called themselves "Classic" Greeks. The Greeks' way of thinking changed, many great artists and philosophers emerged, and dramatic changes would take place. The Hellenic Age brought dramatic political developments (Bruiton). A series of reforms was taking place with the Athenian constitution during the years around the turn of the century. A democratic system of government would ultimately result from these reforms (Burn). A democratic government flourished for the first time in history of the world that an individual could indeed take charge of his destiny (Bruiton).

The Athenians' triumph of the Persians also inspired great confidence and self-assertiveness. Their city, justifiably, would become the sponsor and protector not only for the individual, but of Greece as a whole. The political alignments of the city-states and the art of Classical Athens in the fifth century B.C. from their attitude would have profound consequences (Burn). The statesmen Kleisthenes made reforms. The landed aristocracy and the power of the wealth would be broken. Ten tribes were formed by the people of Athens and Attica. Citizens were now given a voice and the Kleisthenes shattered old power alignments (Bruiton).

In the air was a new sense of individual power and a responsibility that came with it. A sense of power tempered with a calm, careful thought and measured action with full consciousness can be seen in the works of art of the cultural grounds that were made firm (Bruiton). Major developments in Greek painting were seen during the period of the Persian wars. Less dramatic, were the changes in sculptures (Burn). back to top

Hellenic Sculpture

"The beautiful and the good" is a Greek saying in regards to moral goodness of mind and spirit that one's outer beauty reflects. The appeal of classical Greek art helps explain their thought. The Greeks express harmony, balance, and proportioned images that would impart their works of art as something of this greatness of spirit (Bruiton). The Kouros and Kore were still the preferred subjects for free-standing sculpture. Yet, the pieces produced during the Persian wars and the pieces produced during their predecessors profoundly display differences (Burn). The Hellenic sculpture, like the Archaic sculpture, had three phases which were the Severe Style, the High Classical Style, and the Fourth Century Style.

Severe Style

Early Classical sculpture, unlike the Archaic predecessors, began to explore the inner character and the emotions of their subjects. At the same time, they began to create statues that broke away from the rigidity of the Archaic Kouros by assuming a relaxed but balanced pose known as "contrapposto" (Boardman). In this pose, the body turns slightly to one side and its weight rests mainly on one leg and his hip is raised on that side. The head is slightly turned instead of looking straight forward (Woodford).

"Kritios Boy" c. 480 B.C., Ht. 33"

The pose first appeared in a figure known as the "Kritios Boy." In contrast, to a stiff and unthinking Archaic figure, the Kritios Boy seems to twist and tilt in response to what he is thinking. The Early Classical figure also no longer mechanically smiles but seems lost in its own thoughts. The consequences are enormous by these small physical changes. The statue is now alive. This would spark the Classical revolution (Woodford).

Many Early Classical figures are openly emotional, displaying anger or suffering. Early Classical sculpture is also characterized by a new simplicity, for example, the drapery of female figures is planier than the elaborate clothing of Archaic korai. Simplicity of ornament allowed greater concentration on the character of the figure itself. Bronze became the favorite medium of Early Classical sculptures, partly because it was better suited to action poses. The limbs of a marble figure, if extended too far, might break off or throw the statue off balance. Because of the wars, a lot of the pieces were damaged or destroyed and were replicated in marble. The Kritios Boy was originally in bronze (Woodford).

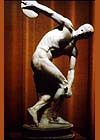

In such works as the "Discobolus" ("Discus-Thrower," 460-450), the sculptor, Myron, depicted an athlete at the moment of greatest

potential energy; just before the figure hurled his discus. Myron's original

bronze is lost, but the sculpture is known through Roman copies in marble. The

statues composition depends on the repetition of circles and semicircles: the

discus, the head of the athlete, and the semicircle of his arms. This repetition

of movement as pattern creates a rhythm that became a leading aesthetic

principle of Greek art (Woodford).

back to top

460-450), the sculptor, Myron, depicted an athlete at the moment of greatest

potential energy; just before the figure hurled his discus. Myron's original

bronze is lost, but the sculpture is known through Roman copies in marble. The

statues composition depends on the repetition of circles and semicircles: the

discus, the head of the athlete, and the semicircle of his arms. This repetition

of movement as pattern creates a rhythm that became a leading aesthetic

principle of Greek art (Woodford).

back to top

High Classical Style

The Classical revolution influenced sculptors to attempt to bring in harmony their theories of proportion, which expressed for the human body the ideal norm with total realism. Books would be written on proportion by sculptors. A canon would be forged and the written treaties made by sculptors about proportions would be used (Boardman). In the High Classical period, this sense of harmony reached new heights in the work of Polyclitus of Argos (Woodford).

Polyclitus wrote a book outlining his theories and, around 440 B.C., made a bronze statue of a nude "Doryphorus" (Spear-bearer) to illustrate them. This statue shows an athlete caught at the moment he begins to take a great stride forward, turning his head to one side and slightly down, and shifting his weight from one leg to the other. A harmonious balance is achieved as straight limbs balance bent ones, and tensed muscles counter relaxed ones. Its sharply defined muscles do no mimic these of a real man, rather, the Doryphorus represents a highly idealized conception of the male figure. Polyclitus devised a precise numerical scheme to determine the proportions of the statue (Woodford).

"Doryphorus"

Fourth Century B.C.

The Peolponnesian war defeated the powerful Athens and weakened the mighty Sparta. For a short time, Thebes gained military ascendancy, but time and influence was limited. The Greek poleis were unable to unite or subjugate permanently no matte how much they tried. No more than nominal independence will the poleis ever be after being dominated first by Macedonia and then by Rome (Woodford).

The Macedonians differed profoundly from the citizens of the Greek poleis even though they were a Greek-speaking people. They lived on the fringes of Greek civilization and were ruled by kings. Philip II had appreciated the good things in Greek culture and ruled from about the middle of the fourth century B.C. He had Aristostle, a renowned Greek philosopher, tutor his son and renowned painters decorated the royal tombs. Philip wanted to avenge the Persians for the early fifth century B.C. invasion and dreamed of leading the Greeks in an expedition against them. By 338 B.C., Philip conquered or made allies of all the Greeks poleis on the mainland through his keen political shrewdness and aptly deployed military might. He was murdered before he could turn his dream into reality (Woodford).

Philip's son, Alexander, then 20 years old, became the sucessor. He would continue the work of his father and later be known as Alexander the Great. Rebellion by the recently subjugated Greek poleis took the first available opportunity against Macedonia domination. Swift and characteristics was Alexander's response. With the exception of the house owned by poet Pindar, the entire city of Thebes was leveled to the ground to serve as an example. This ceased the rebellion (Woodford). back to top

Fourth Century Style

As these events were taking place, occurring at the same time was the transition to Fourth Century Style sculpture. There were three distinguished new trends in sculpture in the Fourth Century Style which was influenced from the second half of the fifth. First, in the direction of naturalism, there was a vigorous new push and an interest in differentiation was revived. In the first half of the fifth century, human beings were characterized in terms of age and personality, but now emotion and mood was added. Second, there was an increase in specialization and artists were included. Artists became fully proficient or skilled in the rendering of passion and portrayed others with gentler emotions and lyrical moods. Third, subjects of art came from new concepts and of abstract ideas. These could be made known through figure of speech, that is, (like Peace) are represented in the human form of concepts, or states of mind (like Madness). Derived from this Greek tradition are the modern personifications such as the figure of the Statue of Liberty and of Brittania on the British penny (Woodford).

The exploration of diversity was shifting away and a shift of emphasis towards the creation of universal ideal was taking place. Pheidas and Polyclitus were two of the greatest sculptors of the age. Their influence and prestige was the main reason for the forward push of this shift. Pheidas was noted for his sublime portrayal of the gods which received praise and noted for the unsurpassed images of men was Polyclitus. By the early years of the fourth century, both men had died. Interest in naturalism, diversity, and characterization was revived with their passing. Its special character of the Fourth Century Style was given by their tendencies and the exploration and elaboration would be continued in the succeeding Hellenistic period (Woodford).

Until the fourth century, no goddess or heroic female figure was depicted completely naked in Greek art. The first female nude was a statue of Aphrodite by Praxiteles that could be also be viewed from behind and considered more erotic than as aesthetic. His male statues seem soft and less manly than the hard-bodied athletes of Polyclitus. Praxiteles also displays uncommon wit. The "Aphrodite of Onidus," for example, is nude because she has been bathing. She covers herself with her hand, as if we, her viewers, have come upon her unexpectedly (Boardman).

The exploitation of all three trends occurred by the citizens of Megara, near Athens when five new statues were commissioned by them for their temple of Aphrodite. An old ivory image of Aphrodite was possessed by them. By the middle of the fourth century B.C., their decision of the sanctuary was to amplify the meaning in almost philosophical terms. Scopas, a sculptor, was asked by the Megarians to create statues representing Love, Desire, and Yearning because of his distinguished representation of passion. Asked to sculpt the gentler figures of Persuasion and Consolation was Praxiteles, who was noted for rendering of the tenderer emotions (Woodford).

Sculptors were encouraged by the Megarians to produce images of emotion and moods which up to this time were explored little in visual arts. The Megarians made the best use of the specialitities of famous artists and finally five different aspects of the goddess Aphrodite were explicitly made. An artistic response to contemporary philosophical thought was to engage in clarifying similar analytic ideas by giving concepts a visible and human form (Woodford).

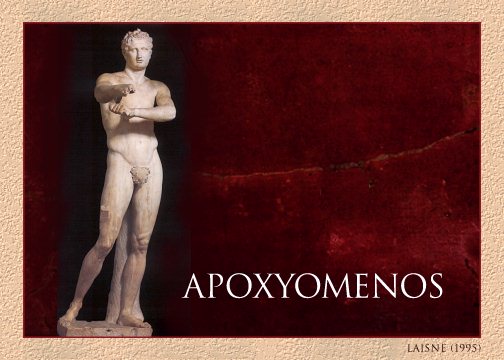

Another important sculptor of the fourth century was Lysippus, who reused the ideal proportions of High Classical works such as the "Doryphorus" by making the heads of his statues smaller in relation to the body. In works such as the "Apoxyomenos" (Youth Scraping Himself Clean), Lysippus extended the statue's arms forward, making the body more three-dimensional and ensuring that the spectator could appreciate the work from every angle, not just from the front. His portraits of the charismatic Alexander the Great, famed for capturing Alexander's character, expressive eyes, and physical appearance of the subject, established a major new type of sculpture, the so-called personality portrait (Burn).

In the fourth century style sculpture, sculptors had achieved the "Trompe l' oeil" realism and could outdo the painters who originally had achieved this effect. Sculpture had become three-dimensional and was life size. There were more twisting compostions and less dominant, was the frontal pose for standing figures.

Deity figures could be distinguished by their attire and gesture and they were either seated, standing, or with a leaning pose. The way the artists, usually sculptors, presented the images is how the Greeks saw them and that determined the image placed on a coin or gem, statue, and relief. By the end of the fourth century, treatises about proportion have been written by several of the fourth century sculptors as did Polyclitus in his canon (Boardman). back to top